Frank Cleary's WWII Service To Our Country

Happy Memorial Day to everyone. This is the story of my Dad’s service during WWII. Frank Cleary was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1919. After graduating from Purcell Catholic High School, he took up photography. He cleaned out the old coal room in the family home and converted that space into a dark room where he processed black and white film and made prints. He attended college part-time and worked for the Wright Aeronautical Corporation as a male secretary. In 1940, the United States reinstated the military draft, and in 1941, Frank was drafted into the Army. He was eligible for a deferment because his company made airplane engines for the Army Air Corps, but as he said, “I had the fever and thought I had a duty to the country. Besides, it was only for a year.” He went to Fort Bragg, North Carolina for basic training and took his camera with him.

The attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, changed his enlistment timeline from one to four years. After basic training, he remained at Fort Bragg, where he worked as a secretary in the Colonel’s office. In the fall of 1942, he said “yes” to an offer to attend Officers’ Candidate School and was off to Fort Sill, Oklahoma. One day, shortly before leaving for Fort Sill, he laid his camera down and left the barracks for a few minutes. When he came back, the camera was gone.

In April 1943, Frank was commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant in the U.S. Army and transferred to the 128th Armored Artillery Battalion at Fort Cooke, California. His division was sent to Europe in 1944 and assigned to General Patton’s 3rd Army. He landed at Utah Beach just over a month after D-Day. No one in his division had yet been to war. His first assignment was as an Artillery Forward Observer in a tank. My Dad had no “forward observing” training. He didn’t know what to do and was scared. His tank was the first in line on the day they prepared to move into battle. He stood up with the top hatch open, watching below him as General Patton walked up to the Division Commander and said, “Your job is to take Brest,” and walked away. The fighting was intense, but my father returned unharmed.

Late in August 1944, Frank was transferred to the 212th Artillery Battalion to become an Air Forward Scout. The 212th had taken many casualties, and the man he was replacing had died in the line of duty. As an adult, he once told me, “At night in my prayers, I would ask, ‘Lord, what are you saving me for?’ That is why I would volunteer for missions. I knew I was saving someone else’s life because I knew I’d be OK.”

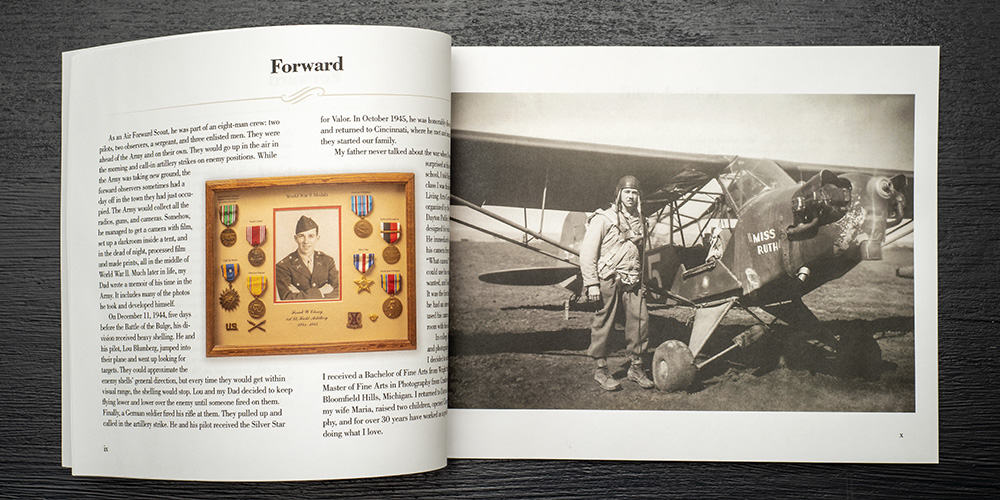

As an Air Forward Scout, he was part of an eight-man crew: two pilots, two observers, a sergeant, and three enlisted men. They were ahead of the Army and on their own. They would go up in the air in the morning and call in artillery strikes on the enemy positions. While the Army was taking new ground, the forward observers sometimes had a day off in the town they had just occupied. The Army would collect all the radios, guns, and cameras. Somehow, he managed to get a camera with film, set up a darkroom inside a tent, and in the dead of night, processed film and made prints, all in the middle of World War ll. Much later in life, my Dad wrote a memoir of his time in the Army. It includes many of the photos he took and developed himself.

On December 11, 1944, five days before the Battle of the Bulge, his division received heavy shelling. He and his pilot, Lou Blumberg, jumped into their plane and went up looking for targets. They could approximate the enemy shells’ general direction, but the shelling would stop every time they would get within visual range. Lou and Frank decided to keep flying lower and lower over the enemy until someone fired on them. Finally, a German soldier fired his rifle at them. They pulled up and called in the artillery strike. He and his pilot received the Silver Star for Valor. In October 1945, he was honorably discharged from the Army and returned to Cincinnati, where he met and married my mother, and they started our family.